Insights into our collections

Design principles of herbarium specimens

A herbarium specimen is a useful scientific resource, but it can also be a source of artistic inspiration, as well as a beautiful work of art.

The 19th-century designer, poet and socialist William Morris once wrote “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.” These words are often quoted in the context of interior design, but the concept can be applied to many other subjects, including herbarium specimens. A herbarium specimen is a useful scientific resource, but it can also be a source of artistic inspiration, as well as a beautiful work of art.

Artists use the rules of design and composition to make artworks aesthetically pleasing. An artwork that is well designed encourages the viewer to look for longer and notice every important detail. The same can be said for a herbarium specimen. Good composition is helpful when it comes to specimens used for research, as it makes finding key morphological characters easier. Specimens that are mounted with this attention to detail in mind may also be more likely to stand the test of time.

Many design principles determine how effective a piece of art is, but among the most important are balance, movement and contrast. Here are a few examples showing how these concepts can be applied to create a stunning herbarium specimen:

Balance

In these examples, balance is created in the composition using colour. For instance, with the Hydrangea specimen, the pale blue flowers are placed on opposite corners of the sheet, with the green leaves in between. This creates a diagonal line of interest across the specimen, allowing us to take in the details of both the flowers and leaves. In the case of the Hellebore, the pink of the three flowers creates a triangle. In combination with the arrow shape of the stems pointing to the base of the sheet, this makes for a satisfyingly balanced composition.

Left: Hydrangea macrophylla 'Setsuka-yae' (L/d)

Right: Helleborus (Rodney Davey Marbled Group) [Moondance] ('Epb 20') (Frostkiss Series)

Movement

The equally spaced parallel vertical lines of the stems in this specimen create a satisfying pattern. This pattern is disrupted by three cleverly placed curving stems, at the bottom left and top left of the paper. These curves together create a leading line, which creates a sense of movement. The eye is drawn from the base of the specimen to the top, before descending back down the vertical lines to the base.

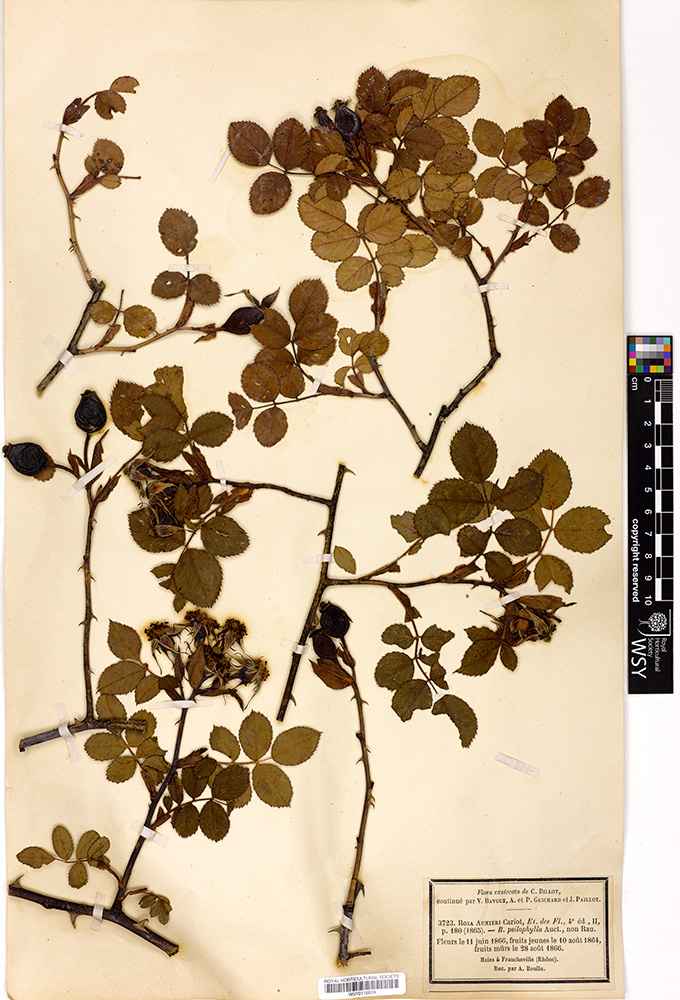

In contrast, the arrangement of plants on this specimen is confusing, with the leaves and fruits of different cuttings overlapping. This means that some features are obscured from view, and there isn’t a clear pathway for the eye to follow to take in each element.

Contrast

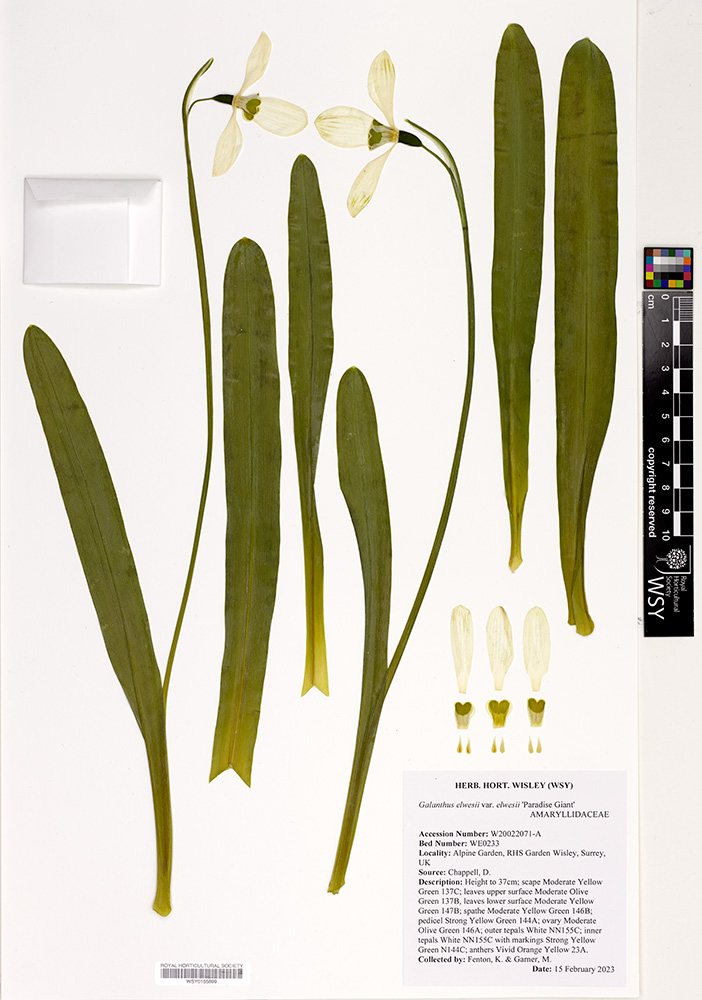

These examples both follow the rules of balance and movement, with plants placed in a way that leads the eye from the base of the sheet to the top. This feeling of balance means that any contrasts between the different elements stands out more. In the Bergenia specimen, the stem of the flower and the midribs of the leaves more or less follow parallel curving lines. Therefore, the contrast of dark purple against paler green stands out more, creating emphasis on both the flowers and the leaves. A similar effect can be seen on the Galanthus specimen, although here the main contrast is with the thickness of the stems compared to the leaves, drawing the eye to the flowers.

Left: Bergenia 'Abendglocken'

Right: Galanthus elwesii var. elwesii 'Paradise Giant'

Botanical art

Botanical art generally uses the same principles of composition as herbarium specimens, as both are 2D representations of 3D plants. Illustrations can also be used on a scientific level – for instance, detailed patterns in flowers can be preserved more accurately in a painting than in a herbarium specimen. In the creation of these paintings, Caroline Maria Applebee considered the composition carefully. The two purple-edged pansies are positioned symmetrically, perfectly balanced with dark green leaves placed above and below. In the other painting, a sense of movement is created with the upright stem of the pale purple Rampion contrasting against the curved stem of the orangey red Scarlet French Bean. This red is balanced by the Garden Tiger moth on the opposite side of the page.

Left: Caroline Maria Applebee, Pansies. A/APP/V.2/98

Right: Caroline Maria Applebee, Rampion : Scarlet French Bean. A/APP/V.1/98

These concepts of balance, movement and contrast can be seen in the way plants are pressed and arranged onto herbarium sheets, but they are present naturally in the plants themselves too. In this way, the creation of a herbarium specimen as both a scientific resource and a work of art can be seen as a collaboration between a curator and a plant.

Author

Saskia Lewis, Herbarium Curator Plants for Purpose, RHS Herbarium

Published

11 July 2025

Insight type

Short read

![Helleborus (Rodney Davey Marbled Group) [Moondance] ('Epb 20') (Frostkiss Series)](../../../pages/33/content/WSY0155927.jpg)