Insights into our collections

Digging deeper in the RHS Plant Collector Archive

Explore how the RHS Plant Collector Archive could form the basis of future research projects.

By Dr Sarah Easterby-Smith (University of St Andrews)

and Dr Elena Romero-Passerin (University of Exeter)

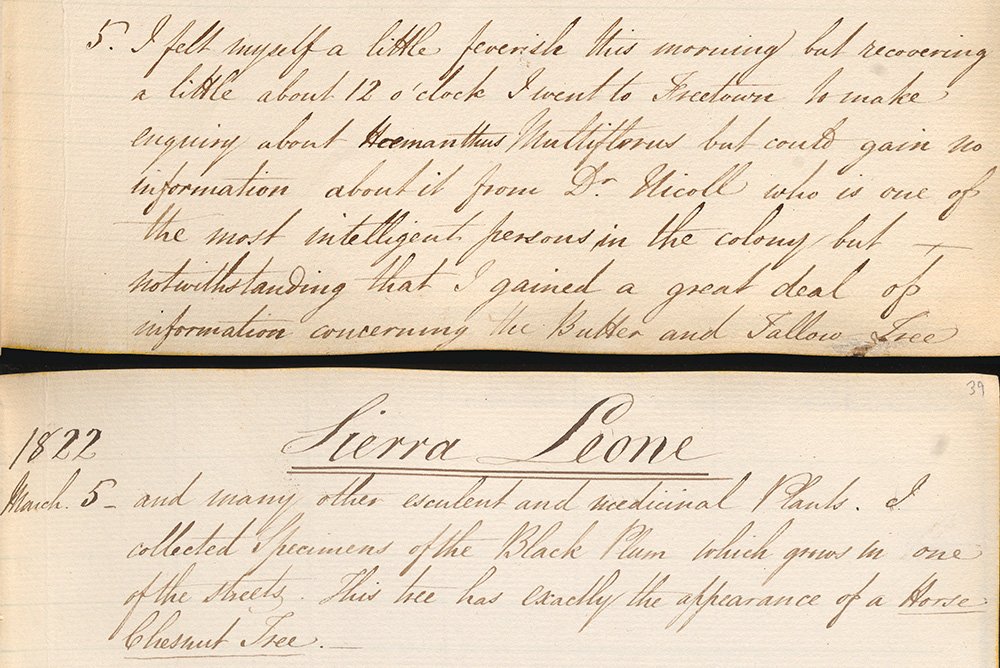

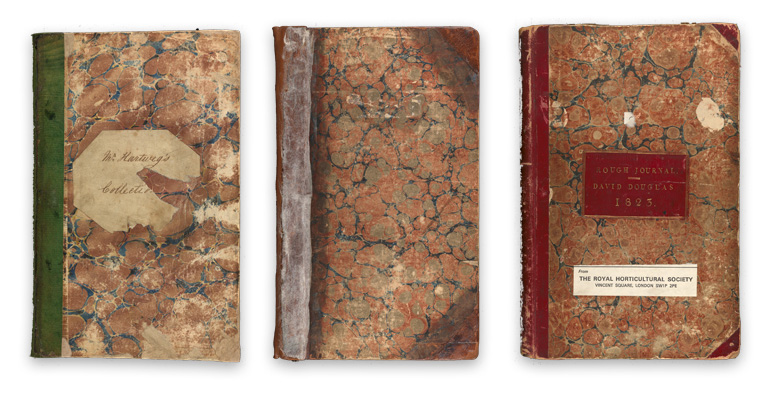

In 2021-2022 we were lucky enough to be commissioned to look at the RHS 19th-century Plant Collector Archive. The material had been recently digitised, and we were asked to investigate its content. What kinds of social histories were buried within? Who did the plant collectors meet when travelling far from home? How did they get along? What did they learn from each other? Separated as we were by the various COVID lockdowns that punctuated those years, we uncovered stories of collaboration and camaraderie, but also colonialism and coercion, in the archive.

Plant collecting as a collective enterprise

The plant collector archive is huge: overall it comprises nearly 4,000 records from 121 collectors, spanning the 19th and 20th centuries. Our investigation focused on the papers of fourteen 19th-century collectors. From these sources it soon became clear that this fascinating collection relates to much more than horticulture alone – through the collectors’ words we learned about the practical pressures of overseas travel and we read some dramatic stories of survival. We also became aware of the new social worlds that they entered, as they ventured far from home.

There is, however, a ‘but’. The archive also contains gaps and silences. We were asked to look for the collectors’ interactions with Indigenous or local peoples. But the collectors were travelling as European imperialism reached its peak. As was the norm at the time for writing of this kind, there is little detail in the collectors’ accounts about the peoples they met. They are rarely mentioned, and rarer still named. Limited observations about their daily life and fleeting mentions of some individuals gave us only an inkling of the often quite significant roles they played in the collectors’ missions.

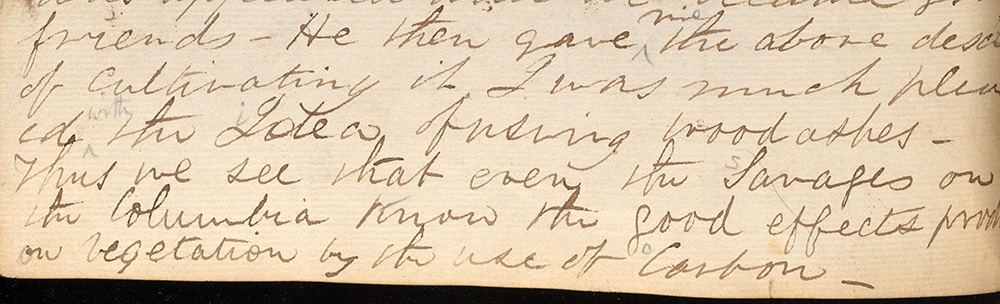

Frustrated, we wondered: how might we develop more inclusive interpretations of 19th-century plant collecting? Contemporary travel and scientific writing conventions restricted what the collectors thought they should record. But by reading the sources more closely (and sometimes, by reading between the lines) we started to see the outlines of much more dynamic social worlds: the alliances, friendships, rivalries and conflicts that shaped these missions. In particular, the journals reveal the extensive practical support that collectors received from people they met. Their words (and their silences) also expose the power imbalances, including forms of oppression, that structured their interactions. European plant collecting, we learned, was never a journey undertaken by a solo traveller; it was always a collective enterprise.

More research, please!

As we read and reflected on the content of the RHS Plant Collector Archive, we came across plenty of material that could form the basis of future research projects. There is much more than one or even two enthusiastic researchers could manage, with topics spanning the social, cultural, environmental, scientific and beyond. Here are just a few of the areas of broader research potential we identified:

There is, of course, masses here that speaks to the expanding literature on colonial botany – including knowledge-making in action, the growth of scientific networks and the practical challenges of plant transfers.

The archive is also an excellent source for global histories of medicine. There is extensive evidence about illness, medical assistance and the medicinal uses of plants, often recorded with a relatively high degree of detail. Within the archive we see how medical knowledge developed and changed as a result of global travel, colonial encounters and cultural interaction.

The plant collectors’ accounts are a form of 19th-century travel writing. There is exciting potential here to explore how literary and scientific tropes conditioned their observations of what they perceived to be the ‘wild’ or ‘domesticated’ landscapes they travelled through. Likewise, the mentions of the European and non-European peoples they encountered, and the societies in which those peoples lived, are heavily framed by contemporary literary conventions.

There is a great deal of evidence too about labour histories. Many of the collectors witnessed, and some engaged with, slavery, the slave trade and indentured labour. Their journals also record fascinating details relating to nineteenth-century geopolitics and diplomacy. The observations of the latter take us far beyond European contexts.

Specialists of the Indigenous cultures that the collectors encountered may also find the archive interesting. Though the record should be read with the collectors’ biases in mind, there is nevertheless information to be uncovered here about the daily life of peoples and, especially, their uses of plants.

Taken together, then, the archive holds huge potential to further enhance or even revise understandings of 19th-century British global history, colonial science and medicine, travel writing and global labour histories – to say the least. Our suggestions are only first impressions – different topics will emerge as the number of people reading this material expands and diversifies. We hope only to have seeded a few ideas for further research – and look forward to watching the conversations about this archive bloom on a much larger scale.

Author

Dr Sarah Easterby-Smith (University of St Andrews)

Dr Elena Romero-Passerin (University of Exeter)

Published

27 May 2025

Insight type

Short read