Insights into our collections

A Garden Fit for a Prince: The lost RHS garden at Kensington

How Prince Albert’s vision shaped a horticultural haven in the heart of Victorian London

A Royal Vision for Horticulture

In 1858 His Royal Highness Prince Albert became the President of the Horticultural Society of London, now known as the RHS. Seeking a more central location than Chiswick, the Society turned its attention to Kensington Gore, a site purchased using surplus funds from the Great Exhibition of 1851. At its heart lay a 22½-acre plot, earmarked for a new garden that would blend horticulture, art and science. By 1859, funding was secured through donations, memberships and debentures. Queen Victoria herself enrolled much of the royal family as life fellows, sparking a surge in applications.

Left: Portrait of Prince Albert, from The Book of the Royal Horticultural Society 1862-1863, p.120

Right: Plan of the Kensington Gore Estate

Building a Garden of Grandeur

The garden’s design was a collaboration between some of the era’s most prominent figures. Architects Francis Fowke and Sydney Smirke worked alongside designer Godfrey Sykes and builder John Kelk. Landscape gardener William Andrews Nesfield created a plan featuring geometric beds, coloured gravel and seasonal plantings. Construction progressed swiftly. By February 1861, the arcades were complete and the Society relocated from St Martin’s Place to its new headquarters.

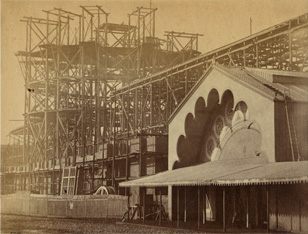

Left: Photograph of the main entrance to the garden under construction, 7 June 1860. RHS/P/KG/2/1

Right: Photograph of the gardens and foundations under construction, c.1860. RHS/P/KG/2/25

A Grand Opening and a Farewell

The garden opened officially on 5 June 1861 with a ceremony presided over by Prince Albert. The ceremony included a procession through the gardens, music by military bands, the planting of a giant redwood and addresses by John Lindley and Prince Albert. Tragically, this would be Albert’s final public appearance; he died later that year in December.

Left: The entrance of the Kensington Garden, from The Book of the Royal Horticultural Society 1862-1863, p.109.

Right: A view of the Garden on its opening day.

A Garden of Wonders

Stretching 365 metres long and 243 metres wide, the garden was arranged across three levels connected by sweeping staircases and slopes. Italianate arcades framed the space while a conservatory at the northern end, dubbed the ‘winter garden’, housed thousands of plants from around the world including Persian lilacs, cotton plants and rhododendrons. Visitors marvelled at fountains, canals, bandstands and even a maze, personally requested by Prince Albert. Nesfield’s elaborate parterres, filled with coloured gravel, proved very popular with visitors and horticultural journalists. A memorial commemorating Prince Albert stood above a cascade and central basin, which became a favourite spot where guests could stop to feed carp and goldfish.

Left: View of the Garden from The Book of the Royal Horticultural Society 1862-1863, p.128. RHS/Ken/9/1

Right: Glass lantern slide of the conservatory at RHS Garden Kensington, 1875-80. RHS/P/KG/5/5

A Grand Stage for early RHS Flower Shows

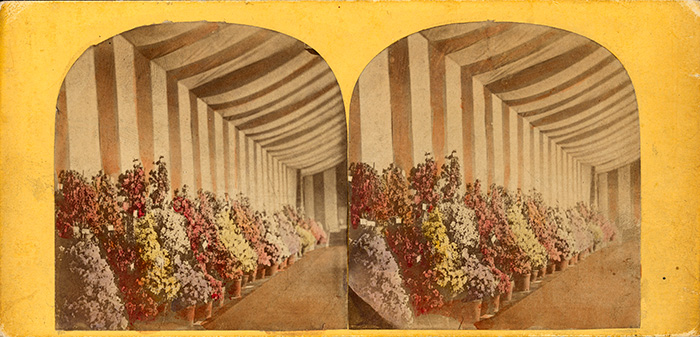

In May 1862, the Kensington Garden became the venue for the RHS’s first Great Spring Show, a precursor to today’s RHS Chelsea Flower Show (whose origins can be traced even earlier to shows held in the Society’s first garden in Chiswick). Specialist exhibitions followed, celebrating camellias, azaleas, dahlias and more. In 1866, the garden hosted Britain’s first International Horticultural Exhibition, drawing over 80,000 visitors in just four days.

Stereograph of the azalea show held in the conservatory at RHS Garden Kensington, 1862. RHS/P/KG/6/1

Art amongst the Flowers

Prince Albert’s vision for the garden extended beyond plants – he wanted Kensington to be a hub for the arts and sciences. A Fine Arts Committee was formed with Albert at the helm, to curate sculptures and artworks for display in the garden. Its annual budget quickly rose from £500 to £1,000 – over £150,000 in today’s money. The garden became a space where horticulture and the arts flourished side by side. However, within a few years there were complaints that the Society's garden was prioritising architecture over horticulture.

Left: Glass lantern slide of 'Queen of the May' at RHS Kensington Garden, 1870-1884. RHS/P/KG/5/4

Centre: Glass lantern slide of 'Nature's Mirror' at RHS Kensington Garden, 1875-1880. RHS/P/KG/5/7

Right: Glass lantern slide of 'St Michael' at RHS Kensington Garden, 1875-1880. RHS/P/KG/5/8

Closure and Legacy

Despite its early success, the garden proved financially unsustainable in the long term. Unable to pay its rent or reduce its debt, the Society vacated the site in 1888. In keeping with Prince Albert’s original vision, the former garden site is today home to Imperial College London and the Science Museum. Echoes of the garden can still be found in Kensington today – including the statue of Prince Albert, which once stood in the garden but now can be found outside the Royal Albert Hall. The garden’s bandstand can also be found in Southwark Park.

Left: Memorial to Prince Albert, from The Book of the Royal Horticultural Society 1862-1863, p.90.

Centre: Glass lantern slide of RHS Garden Kensington from the south, 1875-1880. RHS/P/KG/5/11

Right: Memorial to the Great Exhibition in the Kensington Gore, London, 2013. Via Wikimedia Commons (Chmee2)

Left: Bandstand in RHS Garden Kensington, from The Book of the Royal Horticultural Society 1862-1863, p.205.

Right: The bandstand today, in Southwark Park. Copyright: David Martin. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Discover more

Author

Helen Winning, Project Archivist, RHS Lindley Library

Published

16 October 2025

Insight type

Short read

.jpg)