Insights into our collections

RHS Plant Collector Archive - 19th century papers

Learn more about the RHS Plant Collector Archive, a unique collection of papers associated with 12 plant collectors and their journeys.

From the 1820s to the 1860s, the Horticultural Society of London (as the RHS was then known) sent 12 plant collectors around the world. Their task was to seek out and send back promising plants for British gardens and for scientific study. Seeds, plants, herbarium specimens and information resulting from these journeys contributed significantly to an explosion in the range of plants grown in Britain in the 19th century, the impact of which is still felt to this day.

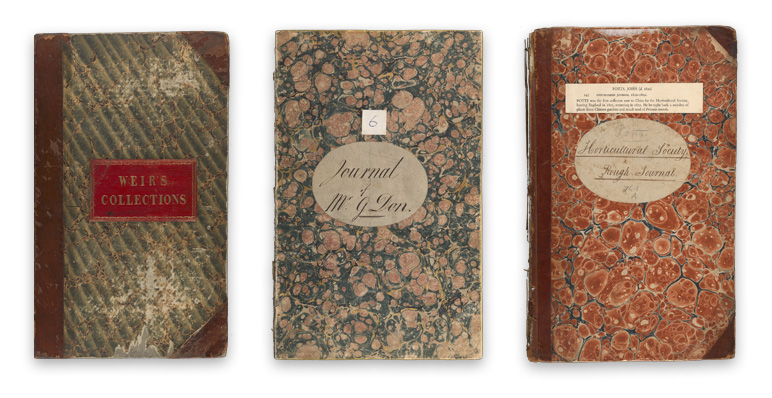

The RHS Plant Collector Archive is a unique collection of papers associated with the 12 plant collectors and their journeys. For the first time they are now fully catalogued, digitised, and free for everyone to access. This has been made possible thanks to the generous support of the Foyles Foundation and the National Heritage Lottery Fund.

The collectors and where they went:

- John Potts, 1821-1822 (China, India)

- George Don, 1821-1823 (West Africa, Caribbean, South America, North America)

- John Forbes, 1822-1823 (East Coast of Africa)

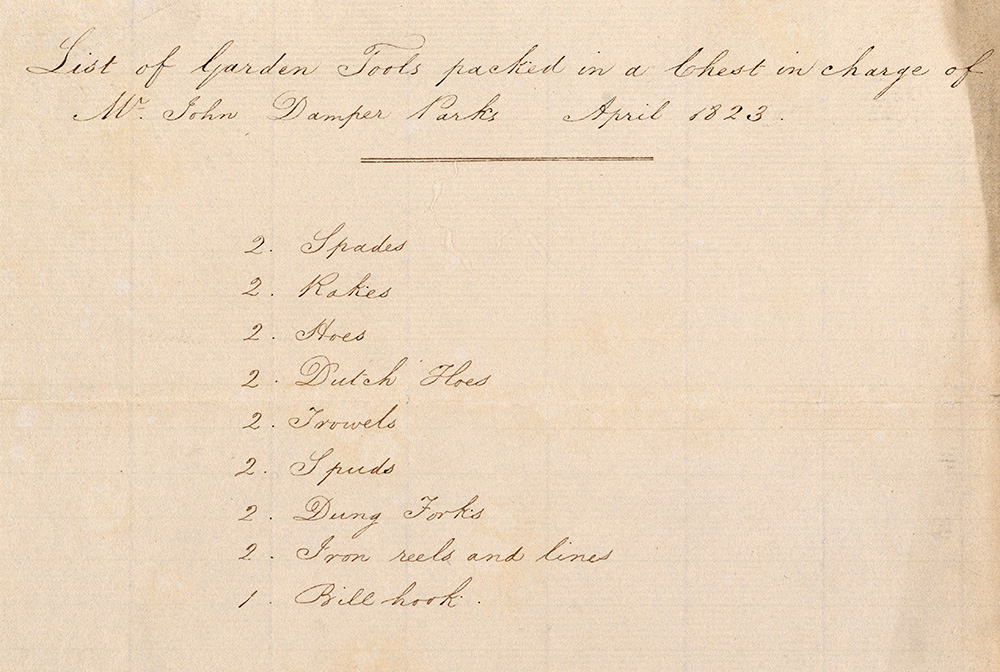

- John Damper Parks, 1823-1824 (China)

- David Douglas, 1823-1834 (North America)

- James McRae, 1824-1826 (Hawaii, South America)

- Karl Theodor Hartweg, 1836-1848 (South America, Central America, North America)

- Robert Fortune, 1842-1846 (China)

- John Jeffrey, 1950-c.1854 (North America)

- Matteo Botteri, c.1854-1856 (Mexico)

- John Weir, c.1861-1864 (South America)

- Thomas Cooper, c.1859-1862 (South Africa)

What does the RHS Plant Collector Archive contain?

The 19th-century papers include travel journals, correspondence, accounts, reference papers and field notes. The collectors were required to keep a journal documenting their journey and findings, and to report back regularly to the Society in the form of letters and copies of their journal, resulting in some cases in multiple versions of both. However, journals do not survive for every collector, and for some expeditions (Botteri, Jeffrey, Weir and Cooper), only records of the plants received in London survive.

The Horticultural Society experienced financial troubles in the 1850s, and large parts of the library collections were sold in 1859. Dried herbarium specimens were also sold in 1856, ending up in collections across Europe (including natural history museums in London and Paris, and universities in Oxford, Cambridge, Göttingen, Montpelier, and Lund).

Despite these losses, the collection is a remarkable and rich resource.

How did 19th-century plant collectors travel?

The Horticultural Society arranged passage on ships, gave the collectors strict instructions on what to look for, and gave letters of introduction to local contacts that would be helpful. Some of the ships the collectors travelled on were sponsored by large trading companies, such as the East India Company or the Hudson's Bay Company. Other collectors joined expeditions with specific aims such as surveying or, in the case of James McRae, the repatriation of the bodies of the King and Queen of Hawai’i. The collectors were restricted at times by the schedules imposed by the ship's captain and their journals reveal their frustration at having to leave promising collecting sites too soon.

William John Huggins, The East Indiaman Asia, c.1836. Courtesy Royal Museums Greenwich.

What was life like for a 19th-century plant collector?

Plant collecting could be a dangerous business, and the collectors spent weeks or months at sea. John Forbes' journey was marred by illness, possibly malaria or yellow fever, which killed a large proportion of the crew he travelled with. Forbes himself succumbed to an unknown illness on the River Zambezi at the age of 23. John Potts died of an unknown illness shortly after his return to England from China.

The role of a plant collector was regarded as a junior one, and the collectors frequently struggled to find their place in the strict internal hierarchy of a ship’s crew, resulting in occasional skirmishes regarding sleeping arrangements and workspace.

The collectors received an annual salary which seems low considering the hardships and dangers they faced. The Society paid their expenses and required them to keep detailed accounts of their spending and expenditure during the journey. These accounts give an insight into their everyday life, recording details of their travels such as hiring boats, employing guides and translators and people to carry or find plants for them.

From the occasional lists of items found in the archive, we know that the collectors were equipped with a variety of items which they had to carry with them. They bought all the equipment for collecting, preserving and studying their plants, and boxes or glazed cases for packing them in. They also had guns, preserving powder (for preserving bird and animal skins), thermometers, maps, pocket compasses, and even a sword. David Douglas's journal includes frequent references to clothing, including a tartan coat and deer-skin trousers. There are also references to other items for everyday use: razors, Windsor soap, brush, towels, tea kettle and medicines such as calomel and laudanum.

Plant collecting in the British Empire

Plant collecting in the nineteenth century relied heavily upon the trade and transport networks of the British Empire. The main objective of collecting missions was to acquire new plants or varieties which would be commercially viable in Britain, either as ornamental garden plants or edible fruits. Collectors sometimes carried European seeds with them to help supply the food they were familiar with or introduce crops which might be commercially exploited in new territories.

The expeditions were mostly to British colonies, although some of the collectors also visited colonies of other European empires, such as Mozambique and Brazil, which were under Portuguese rule, or the Spanish colonies of Latin America.

Many of the expeditions were conducted in places where the trade in enslaved people was still legal or had only recently been abolished. George Don, who travelled in the early 1820s, stayed with a slave owner in Jamaica, and mentions the abolition of slavery in the British colonies, including Sierra Leone, which at the time of his travels was a British colony for freed slaves. He travelled aboard Royal Navy vessels (HMS Iphigenia, and from Sierra Leone onwards, HMS Pheasant) tasked with intercepting slave ships across the British Empire. James McRae and John Forbes reported on an enduring slave trade in Brazil and Mozambique respectively. Forbes bought enslaved people for his final journey on the Zambezi, with the intention of freeing them on their return. It is not known what happened to these people after Forbes’ death.

Who helped the plant collectors in their work?

The plant collectors met and interacted with a wide variety of people. Many of their initial points of contact were British and European colonial government officials and traders introduced to them by the Society. They often helped to orient the collectors and connect them with local people who could help them further.

Although some of the collectors provide rich cultural details regarding the life of the local people they encountered, they rarely name or describe the contributions of those that they hired to play vital roles in their expeditions (including as plant collectors, guides, translators and labourers). Exceptions to this rule are often kings and chiefs.

The collectors sometimes record in their journals the indigenous names and uses for plants that they gathered from conversations with local guides, but this information was often not included in the final versions of their publications. We hope that the digitisation of the archive will enable researchers to find stories that have been previously hidden or ignored.

What did the plant collectors collect?

The plants the collectors acquired came from a variety of growing environments. In addition to collecting plants from their natural environments, the collectors also obtained plants from local people in gardens, nurseries, apothecaries and markets. Live plants and seeds were shipped to the Society's gardens at Chiswick and later at Kensington, where the gardeners were charged with growing them - often with very little information to help them. Acquisition books record the plants sent by Karl Theodor Hartweg, Matteo Botteri, John Jeffrey, John Weir and Thomas Cooper. In the case of Botteri, Jeffrey, Weir and Cooper these are the only records of their activities held by the RHS.

Plate 1078. Camellia reticulata. Edward’s Botanical Register 13 (1827)

Difficulties in shipping plants

Keeping plants alive during on long overseas journeys was an arduous task, and plants often perished due to careless handling or exposure to extremes of temperature, sea water, insects and rats. There are frequent references in the papers to attempts to improve the design of the boxes used to transport the plants, and debates as to the best location on the ship to keep different plants and specimens. The development of the Wardian glazed cases helped matters, as they offered protection while enabling light to reach the plants. In the absence of glass, transparent oyster shells were sometimes used as a substitute. Robert Fortune was one of the first plant collectors to use Ward’s invention to send living plants back to England.

Our approach to cataloguing and describing the papers

The plant collector papers reflect the culture and beliefs of their authors and they contain frequent use of pejorative language that may be offensive. For this reason, some material on this site carries a content warning. For details of our approach to cataloguing this material, please see our full terms and conditions.

Further research

We hope that sharing this archive under a creative commons licence will open the archive as a resource for researchers across the world. We would be delighted to know about any research projects utilising this collection. Please contact our library enquiry service if you require any further assistance and see our full terms and conditions regarding publication of images from this collection.

Author

Fiona Davison, Head of Libraries and Exhibitions, RHS Lindley Library

Published

9 May 2025

Insight type

Long read

.jpg)

.jpg)